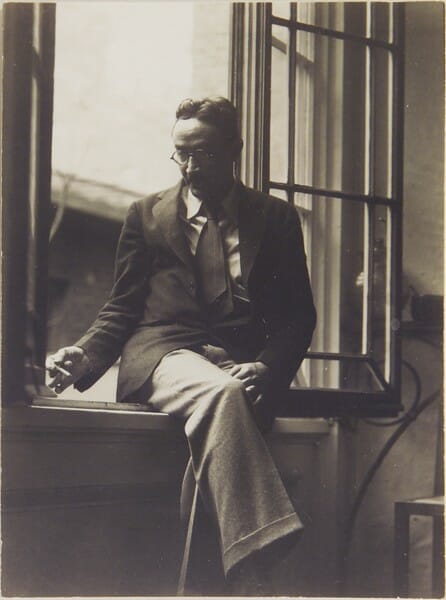

Jean Toomer, 39 West 10th Street, New York, Spring 1934. Photo by Marjorie Content; Image courtesy of Jill Quasha, New York. Copyright: Estate of Marjorie Content.

In an earlier post we highlighted the achievements of Marjorie Content (photographer, friend, and client of Wharton’s) in which we made brief mention of her husband, Jean Toomer. After the recent reemergence of Toomer’s “prohibition briefcase” in our museum collection during off-season cleaning we felt compelled to revisit this connection!

Jean Toomer (1894-1967) was a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance. His most well-known work, Cane, is a collection of thematically linked character sketches, prose poetry and short stories revolving around the complexity of African American life from North to South. Published in 1923, Cane received critical acclaim and is now considered a classic of Modernist literary experimentation. Interestingly to those of us following the Esherick thread, Toomer listed Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio among his influences (Sherwood Anderson and Esherick were longtime friends).

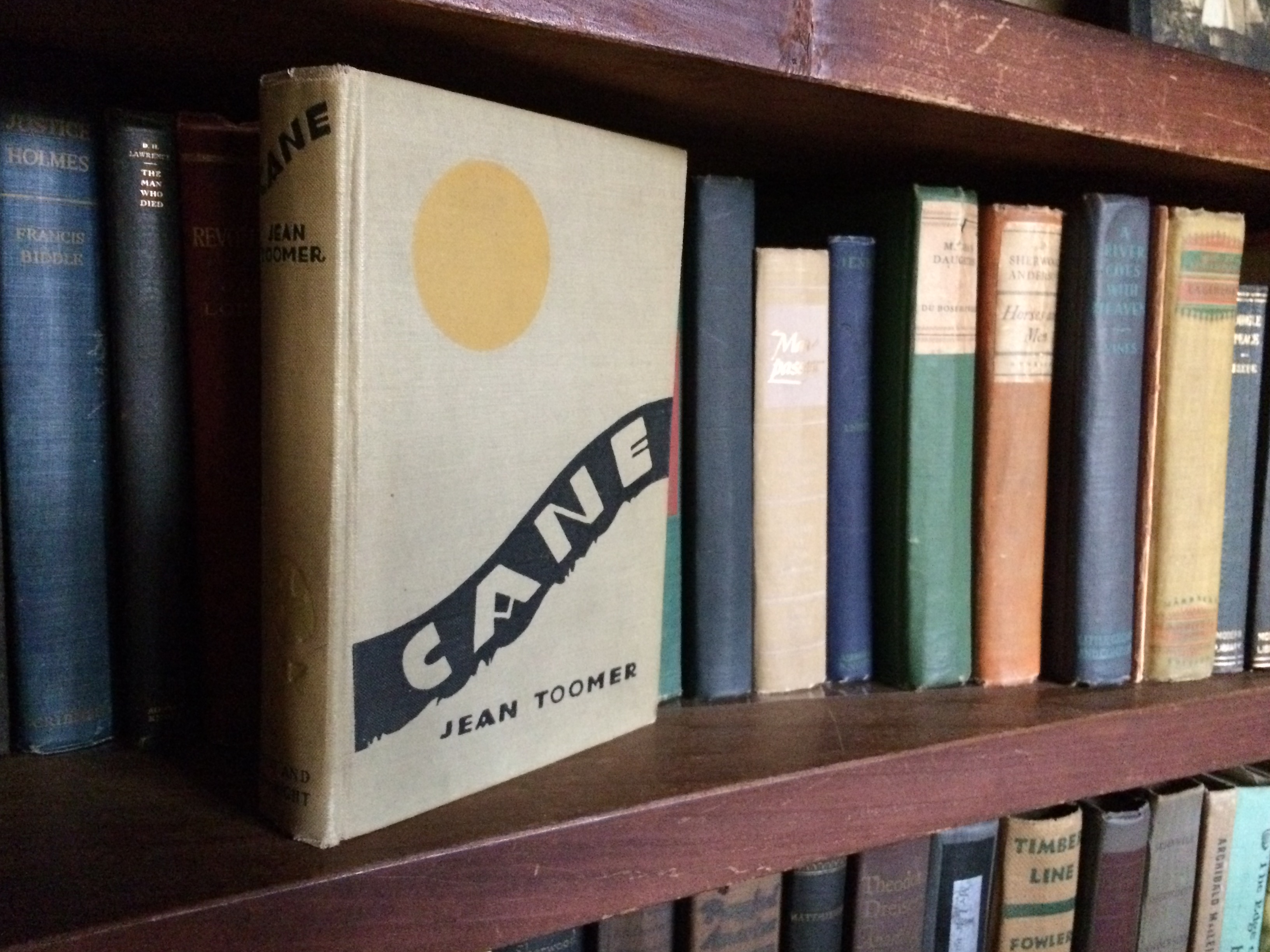

Snooping through the shelves in Esherick’s bedroom one can find two copies of Cane – the 1923 edition and a 1969 reprint that revived interest in Toomer’s lyrical vignettes. In both copies Esherick had stuffed newspaper clippings about Toomer highlighting the re-release of his most famous work. Esherick had come to know Jean Toomer through Marjorie Content who married Toomer in 1934.

We should note that the complex nature of highlighting Jean Toomer for Black History Month is not lost on us. Toomer, who was multiracial, resisted being categorized as an African-American author and was determined to transcend these definitions. He considered himself the personification of the “New American,” neither black nor white, and was far more concerned with achieving internal spiritual harmony. This spiritual journey eventually led him to join the Quakers.

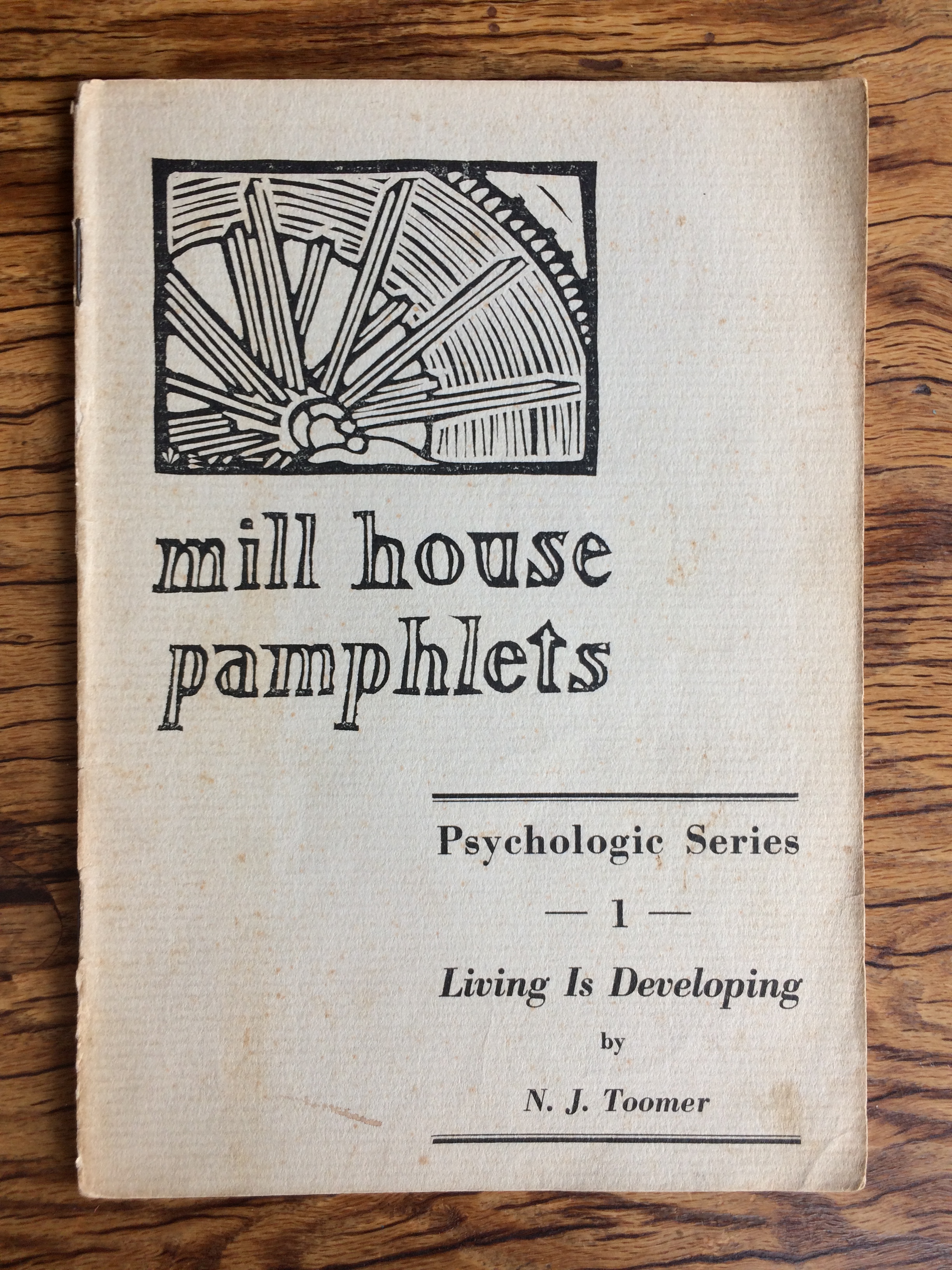

The Toomers had moved to Mill House, a farm on the outskirts of Doylestown, within a year or so of their marriage and joined the Quakers soon thereafter. Esherick was enlisted to help convert a barn on the property into their home, with Esherick and Content working together on the project. Toomer’s interests had shifted by this time in his life, and he was withdrawing from the public eye. Toomer and Content began a philosophical press from their home, Mill House Press, to publish his writings and ruminations on the nature of humankind. These pamphlets, which feature a woodcut of a water wheel by Esherick on the cover, are also marked by Toomer’s return to his “full” name – Nathan Jean Toomer, signifying to many the departure from his earlier work. (It’s worth noting his name was actually Nathan Eugene Pinchback Toomer – so he had plenty to pick from.)

Toomer’s later booklets, from the 1940’s, focus heavily on his interpretations of Quaker faith and worship. Esherick had several of Toomer’s publications from this period on his shelves as well, warmly inscribed “to the one and only Wharton” or “From one old salt to another, Jean.” How Esherick came to own Toomer’s leather briefcase remains a bit of a mystery. However, it certainly highlights the unusual path that Toomer’s life took. After all, these Quaker pamphlets are a long way from the raucous and roaring 1920’s when Toomer was breaking ground with his experimental prose.

Check out our March 2013 blog post for more info on Marjorie Content and her connection to Wharton Esherick.

More information on Jean Toomer can be found at poetryfoundation.org

Post written by Visitor Experience and Program Specialist, Katie Wynne.