On September 15, 2022, the Wharton Esherick Museum opened the third and final temporary installation of our 50th anniversary year celebration, Home as Stage. While Home as Stage is an exciting milestone for WEM in several ways, it is especially notable that this marks the first time the museum has hosted multiple contemporary artist installations within Esherick’s Studio. The four Philadelphia-connected contemporary makers on view – Emily Carris-Duncan, Kay Healy, Colin Pezzano, and Stacey Lee Webber – create works that engage with ideas of craft, domesticity, legacy, and creative labor. These ideas still permeate Esherick’s space and the ways in which we understand the objects it holds.

On behalf of WEM, I invited Duncan, Healy, Pezzano, and Webber to spend time in the studio and its archives in the winter of 2022. During that time, they developed their own connections to Esherick’s space and story based on aspects of his personal narrative and the physical and material nature of the campus. Depending on their learning and how their findings related to their existing practice, each artist chose to either select existing work or create new objects to integrate in Esherick’s Studio for just a few short months.

You can read more about the Home as Stage artists’ biographies, the works they chose for the exhibition, and their own words about the experience on our online exhibition page, linked here. Below, I’ll take you behind the scenes to learn more about each artist’s process and time at WEM.

Emily Carris Duncan

Emily is an artist and educator whose work largely focuses on textile techniques. They are the co-founder of The Art Dept Collective and High Pastures, a new nonprofit interdisciplinary studio and retreat space dedicated to supporting the work of marginalized creative practitioners in Vermont. Emily’s time on WEM’s campus took place through a mix of in-person visits and Zoom calls. While they have strong Philadelphia ties and is the co-founder of The Art Dept Collective, a Philadelphia-based artist space, recently Emily has begun to split their time between the city and Vermont, where they’re building a new nonprofit interdisciplinary studio and retreat space dedicated to supporting the work of marginalized creative practitioners. Emily’s work for WEM was made in that new space.

Emily Carris-Duncan used natural materials as dyestuffs to make her piece for Home as Stage. In this shot, we see her in her home studio in Vermont.

The desire to build a more rural life in the service of art was one of the first overlaps with Esherick’s narrative that Emily uncovered during our conversations. Also resonant with Emily was Esherick’s deep appreciation for the potential of partnerships – with other artists and tradesmen, his family, and his community – for an expanded creative practice. Delving into the story of Ed Ray, Esherick’s wood supplier and longtime collaborator, Emily decided to use woods from the WEM campus as a source of natural dyes in the quilt she created for Esherick’s Studio Bedroom. Working with WEM staff to identify woods that Esherick used in his practice and which were available from trees onsite, WEM’s campus is physically integrated into Emily’s work in a tangible – and beautiful – way.

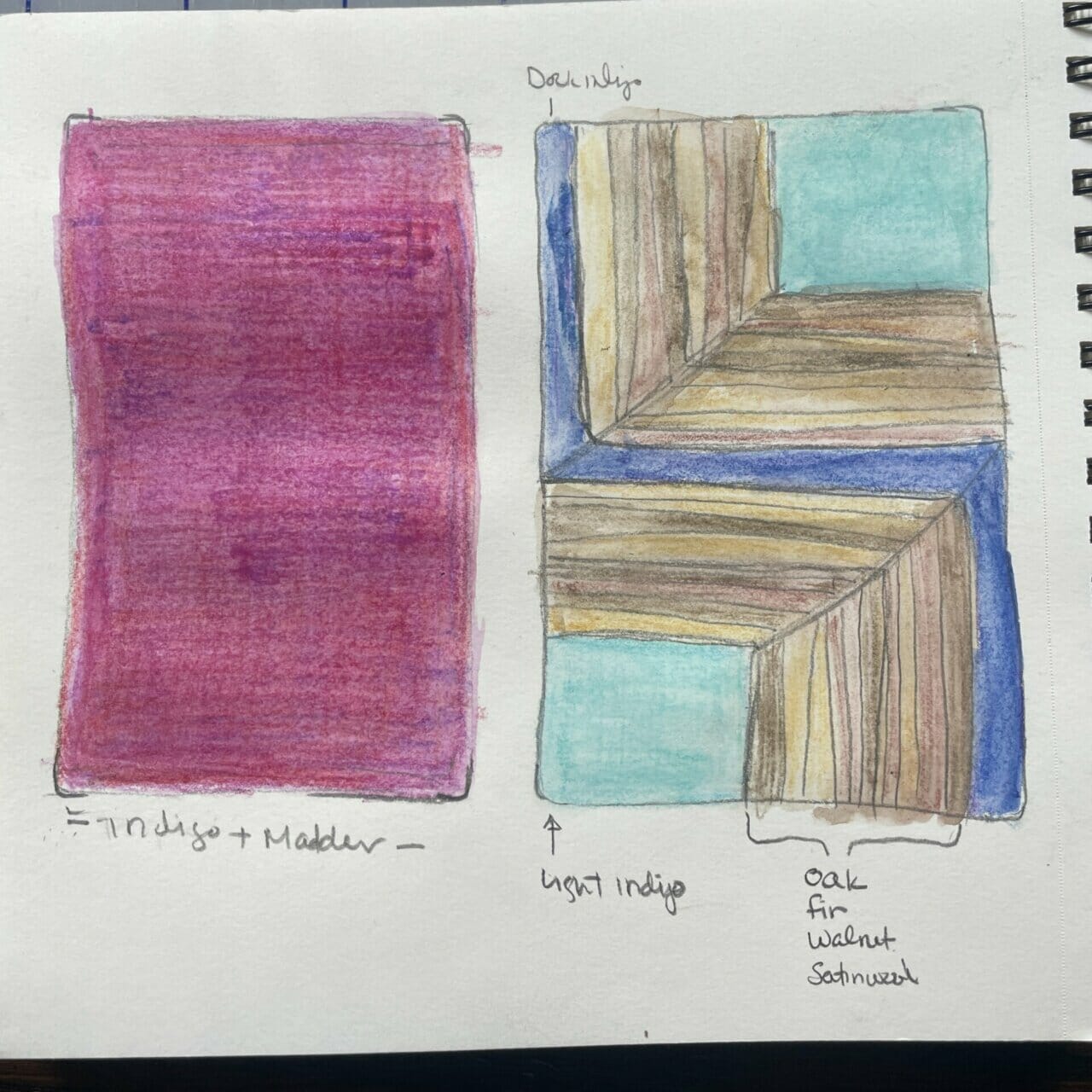

Emily Carris-Duncan shared drawings like this one, which maps out the design of her quilt and the dyes she hoped to use, during the making process.

Kay Healy

Kay Healy began her time working with WEM with several visits to the site, intrigued in particular by the stories of the women in Wharton Esherick’s life whose presence was integrated throughout the Studio even if their stories weren’t being explicitly told in its interpretation. Kay’s larger artistic and creative practice focuses on creating life-sized drawn, painted, and screen-printed fabric installations of objects that investigate themes of home, loss, displacement, and resilience. These are often based on interviews with people about the objects that matter deeply to them (you can participate in a new interview project of Kay’s designed specifically for Home as Stage here). Many of the objects from her previous work that have been integrated into the WEM site are female-coded, suggesting specific roles, labor, and expectations, especially around caretaking.

Kay Healy and WEM Curatorial Assistant Alex Till on installation day in the Studio’s Kitchen.

Onsite, Kay and I talked about Letty Esherick and pulled out the cache of clothes, textile samples, and other materials related to Letty’s own artistic practice that were recently rediscovered in Esherick’s 1956 Workshop Building. Kay was also drawn to the stories of other women who might be seen as being on the periphery of Esherick story: his major patron Helene Fischer, who was instrumental in the early years of his woodworking career; Anne Tyng, whose philosophies undergird the design of Esherick’s 1956 Workshop even if only Esherick and Kahn’s names are on the building; and Miriam Phillips, Esherick’s longtime partner of his later years who lived in the Studio both during and after his lifetime. Onsite, Kay used what she learned about Miriam Phillips to create an object that’s a universal symbol of cohabitation to give her a new sense of belonging in the Studio space. A toothbrush, modeled after period designs from the 1960s, marks Miriam’s continued presence and impact on the narratives we share at WEM, long after her passing.

Kay Healy wrote this about the object Kay’s Spectra Pumps, now on view in the refrigerator at WEM: Kay’s baby was born in October of 2020 and she breastfed and pumped for over a year. The process was incredibly time consuming, and took an estimated 48,600 minutes or 33 full days of pumping and breastfeeding around the clock.

Kay Healy made two toothbrushes to coexist in Esherick’s bathroom, one for Miriam and one for Wharton.

Colin Pezzano

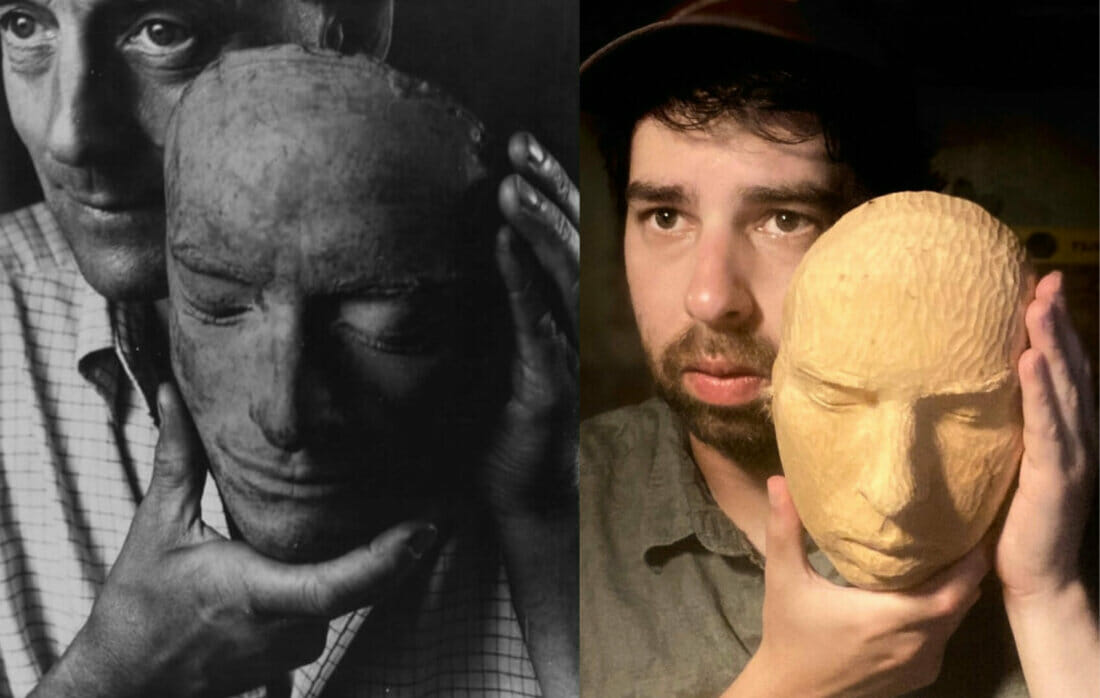

Even though Colin Pezzano had been to WEM numerous times since first learning about Esherick during his time at the University of the Arts, he expressed a new insight during every conversation he and I had in the Studio together. A longtime Esherick enthusiast – so much so that he carved his own life mask and posed with it in a photograph inspired by a similar image of Esherick! – Colin and I spent a good amount of time discussing Esherick’s work as an illustrator and printmaker, especially the way in which he balanced image and object in his work. This was, in part, because of a current project of Colin’s – Soma, a graphic novel in woodcuts, which is available via the WEM Store – but also because of the way Colin explores the same tensions in the trompe l’oeil objects he creates.

Colin Pezzano sits at Wharton Esherick’s Dining Room Table while installing his piece for Home as Stage.

I was lucky enough to visit Colin’s studio in the basement of his home. Together, we discussed what made sense to bring to WEM’s campus. We were not just surrounded by the objects in question, but also by the specter of process: tools in various phases of use, artworks in various stages of completion, and materials that had yet to be transformed into their final iteration. In discussing his process and what it means to integrate life and work in the same space, we moved towards bringing a moment of Colin’s process into Esherick’s finished Dining Room. The objects that visitors see on the table include many kinds of Colin’s tools – from a T-square to an index card to an ipod – recreated meticulously in wood. They are displayed so that we feel as though we’re walking into a moment of process from which the artist – Colin or Wharton – has just slipped away.

Onsite at Colin Pezzano’s Studio in South Philadelphia.

Colin Pezzano and Wharton Esherick’s Life Masks, side by side.

Stacey Lee Webber

When artist Stacey Lee Webber visited the museum for the very first time in February 2022, she found a campus in productive disarray: WEM was in the midst of a massive – and necessary! – tree removal project around the studio and workshop. However, arriving on a campus thick with tools, machinery, and people at work didn’t phase Stacey. Not only does Stacey operate her own workshop with multiple practitioners working in support of her vision out of the Globe Dye Works building in Northeast Philadelphia, she has also been exploring the idea and form of tools for years in her own sculptural practice. In fact, seeing chainsaws and heavy machinery onsite that day shaped the conversation that Stacey and I had about her potential contribution to Home as Stage: a chainsaw, constructed entirely out of pennies, that she had begun working on four years prior, but hadn’t had the space or time in her busy schedule to complete.

Stacey Lee Webber in her Studio at Globe Dye Works

This was a happy moment of synchronicity. Chainsaw is a part of a series of immaculately crafted penny tools begun in 2008 that started with basic hand tools (hammer, screwdriver) and moved towards more mechanized tools. Our conversation onsite made it clear that the creation of Stacey’s new piece would be inextricably tied to its debut at WEM, and we spent time looking through the evidence of tools and making onsite at the museum (including Esherick’s unconventional handmade bandsaw and his printing press). Stacey’s finished Chainsaw is now on view in the Main Studio, which is styled as a display and living space, even though it’s where Esherick did the majority of his creative work in wood between 1926 and 1956. Bringing her contemporary sculptural tool back into a space in which Esherick built so many important objects feels like a full circle moment.

Stacey Lee Webber’s Chainsaw (The Craftsman Series), 2022

Esherick’s Studio Interior with Essie and his tool bench, 1930s

Intrigued by these behind the scenes stories? We invite you to come see Home as Stage at WEM through December 30, 2022 or spend some time with programs featuring these four artists.

Post written by Emily Zilber, Director of Curatorial Affairs and Strategic Partnerships.

September 2022