This month’s blog post was written by Lynne Farrington, Curator of Printed Books at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of the University of Pennsylvania.

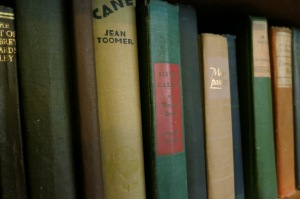

Like so many Americans through the years, Wharton Esherick owned—and presumably read—banned books. An examination of the list of his books now housed at the Wharton Esherick Museum—and one should NOT assume that these are the only books he owned, let alone read—reveals that he had in his library books that were banned or prohibited in at least some parts of the country, if not the entire country, at one time or another. Some were by important American writers like Thoreau and Whitman, both of whose works encountered censorship at different times. Perhaps more importantly for Esherick, some of these banned books were works by friends of his, including Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson, or by writers with whom he would have become acquainted through them or through his visits to Philadelphia’s Centaur Book Shop.

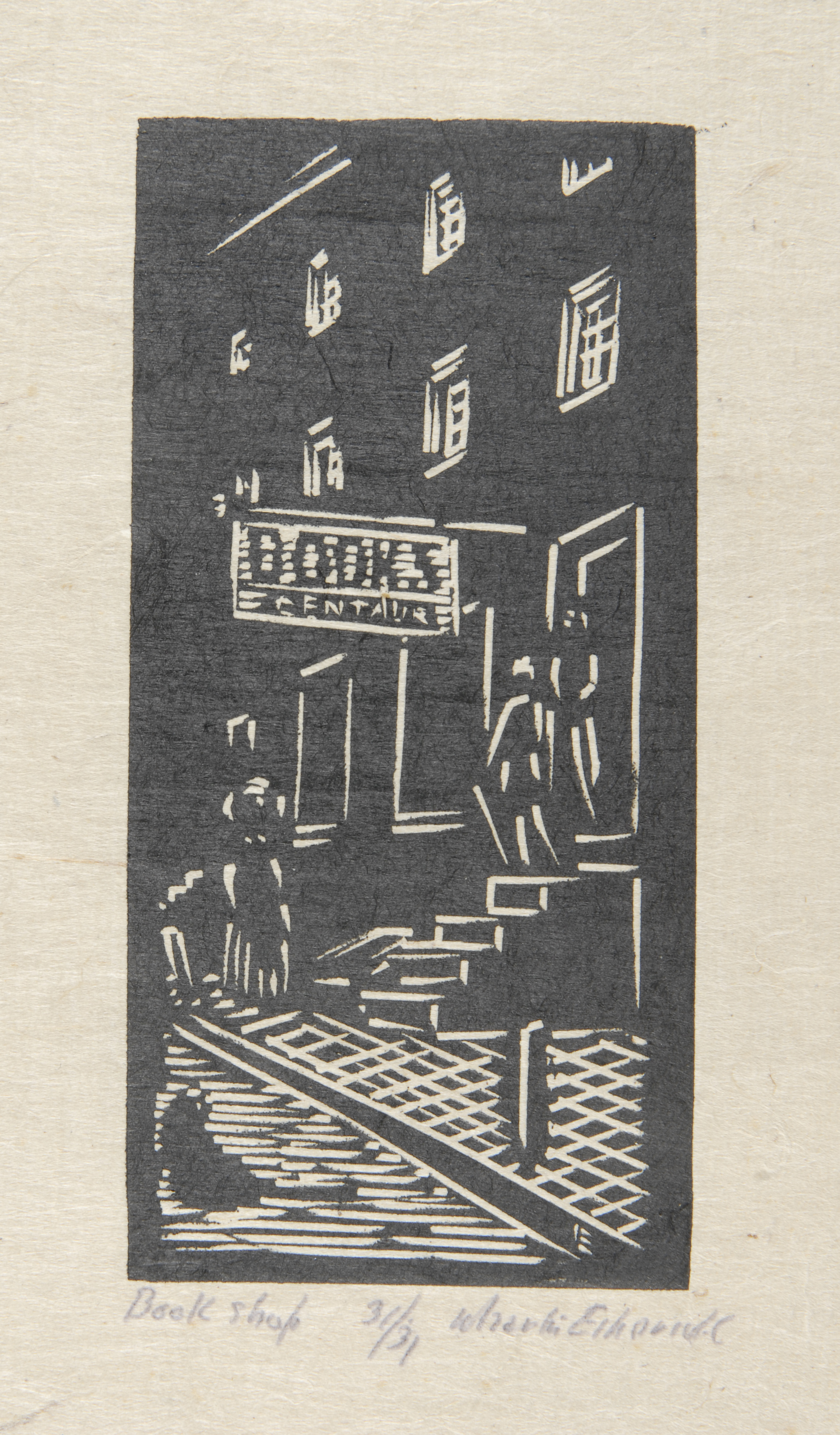

The Centaur Book Shop’s stock focused on modern literature, including first editions, limited editions, fine printing, and signed copies, as well as art books and an assortment of literary and philosophical magazines. The name for the bookshop came from a line (“‘Up on my back,’ said the Centaur, ‘and I will take you thither.’”) in James Branch Cabell’s novel, Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice (1919), which had been denounced by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. According to Harold T. Mason, proprietor of the Centaur Book Shop, the reference “lent an air of mild wickedness to the enterprise,” although Mason himself did not find the work particularly obscene.

The Centuar sign Wharton made for the Centaur Book Shop, 1924. Currently on display at the Wharton Esherick Museum.

However, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice brought a case for obscenity against the book. The printing plates were seized in early January 1920, preventing the printing of additional copies. There were protests, leading to the formation of the Emergency Committee Organized to Protest Against the Suppression of James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen. A published report of the Committee, Jurgen and the Censor (1920), included contributions by Cabell and such well-known writers of the time as Sinclair Lewis, H.L. Mencken, Kate Douglas Wiggin, Padraic Colum, Christopher Morley, and Theodore Dreiser. The legal proceeding against Cabell and his publisher ultimately failed, and they were cleared of all charges. Ironically, suppression of this novel only generated greater interest in the book, thereby increasing rather than decreasing its circulation.

Harold Mason, in acquiring books for the Centaur’s shelves, would have occasion to—stock, import, or smuggle, you choose—and sell a number of prohibited works, including Joyce’s Ulysses and Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover—under the counter, of course. On December 20, 1929, D.H. Lawrence’s controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover was banned in the United States. Even before it was officially banned, however, Lawrence himself knew there would be controversy surrounding this work, and so he had the first edition privately printed in Italy.

Lawrence and Mason knew each other and corresponded in the late 1920s, in part as a result of the Centaur’s publication in 1925 of both A Bibliography of the Writings of D. H. Lawrence by Edward D. McDonald and a book of Lawrence’s essays, Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, for which Esherick did the well-known woodcut of the porcupine that graces the half-title page. D.H. Lawrence’s correspondence with Mason, McDonald, and the Centaur Book Shop and Press was acquired by the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas, Austin, and published as The Centaur Letters (University of Texas, 1970). Lawrence mentioned that he was privately printing Lady Chatterley in his 18 Dec 1927 letter to Mason, claiming that he is doing so because no publisher would dare, it being shocking “from the smut-hunting point of view,” so much so that “the Puritan will want to smite me down” (Centaur Letters, p 31). His greatest fear, as he expresses it later in the letter, “is your damned interfering censorship” (Centaur Letters, p 31), about which Lawrence asks Mason for his advice. In a subsequent letter, that of February 1928, Lawrence recognizes that he will not be able to get Knopf to publish an unexpurgated edition, so he says he’s “going to try to expurgate and substitute sufficiently to produce a properish public version” even as he plans to publish his own “unmutilated version” (Centaur Letters, p 32).

Lawrence writes to Mason in early July 1928 to say that the printer is mailing him a copy and tells him he’s grateful for getting him orders. Presumably some of the books did arrive safely in Philadelphia. In his letter of 6 September, Lawrence tells Mason that he believes the

publisher “shipped in all about 140 copies to America. How many are lost, I don’t know. But we know a fair number arrived” (Centaur Letters, p 35). There also appears to have been a pirated edition that Lawrence refers to in his 31 May 1929 letter, “produced in Philadelphia—& is now in second edition—& two different sources told me you were back of it—which I was very loth [sic] to believe” (Centaur Letters, p 36). The letter indicates that Mason had previously written to assure Lawrence he had nothing to do with it.

Unlike Jurgen, which Esherick knew and presumably read, even though it does not appear on the list (another Cabell work, Figures of Earth (1925) does), he clearly owned a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, in a privately printed edition from 1928 (Book no. 20). Was it acquired from the Centaur Book Shop? It would seem likely that it was, given the role of Harold Mason played in smuggling copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover into the country.

Theodore Dreiser’s realistic novel Sister Carrie, about a working class girl who moves to the city and pursues her version of the American Dream through the manipulation of men, was the first of his works to face censorship. Dreiser must have been aware that he had written what would be a difficult work for a major American publisher to publish. Turned down by Harper and Brothers, he then submitted it to a new firm, Doubleday, Page & Co., from whose junior partner Walter Hines Page he received a gentleman’s agreement to publish the work. However, when Frank Doubleday, the senior partner, read the typescript, he reacted negatively to the narrative, considering it “immoral,” and pushed not to publish it. Dreiser, though, demanded its publication, and upon receiving legal advice that it was bound to do so, the firm proceeded to publish it in 1900, but not before they censored the text, producing a cut and bowdlerized version of the original manuscript. In addition, to avoid bringing attention to the novel, Doubleday bound it in a non-descript red-cloth binding and then refrained from marketing it, in effect suppressing it. With fewer than 500 copies sold, it was essentially a failure.

When Dreiser himself had Sister Carrie reprinted in 1907, he did so using the expurgated Doubleday version. Harpers then republished it in this form in 1912. The cut and censored material was not restored until the University of Pennsylvania Press edition, published in 1981, went back to the original manuscript to recover as much of Dreiser’s original work as possible, thereby revealing the nature and extent of the Doubleday’s censorship. Esherick’s copy was of the 1917 Modern Library edition (Book no. 376).

Two other works by Dreiser also faced censorship, The Genius and An American Tragedy. After The Genius, published in 1916, was brought to the attention of the head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and banned for being blasphemous and obscene, the publisher voluntarily agreed to withdraw the book. Dreiser found a new publisher, who republished it in 1923, without challenge. An American Tragedy, published in late1925 by Boni & Liveright, was threatened with legal action in 1927 by the district attorney in Boston on the grounds that it endangered the “morals of youth.” The publisher, seeking to challenge this threat, convinced a Boston bookseller to sell the book. The bookseller was then arrested and fined. Although the famous defense lawyer Clarence Darrow—hired by Horace Liveright to help in the defense of Dreiser in his fight for freedom of expression, was involved in the appeal to the Massachusetts Supreme Court—it was unsuccessful and the bookseller was convicted of “selling an obscene, indecent, and impure book.” While Esherick had many of Theodore Dreiser’s works on his shelves and likely had read these as well, neither of them are on the list of books currently at the Museum.

On a final note, Esherick’s good friend Sherwood Anderson also encountered censorship in the publication and dissemination of Winesburg, Ohio, a work that challenges the mores of small town America. John Lane, who published Anderson’s first two novels, refused to publish Winesburg, Ohio and it was banned in the public library in Anderson’s own town of Clyde, Ohio. Not surprisingly, Esherick had a copy of the first edition, published in 1919 (Book no. 423). So, it would appear that Esherick was very much part of a world in which censorship was alive and well.

For more information:

On Lady Chatterley’s Lover:

http://literarycornercafe.blogspot.com/2010/12/today-in-literary-history-lady.html

On Sister Carrie:

http://www.library.upenn.edu/collections/rbm/dreiser/scpubhist.html

On censorship and banned books:

On banned book week:

http://www.bannedbooksweek.org

Note from the author Lynne Farrington:

When considering censorship, it’s important to recognize that censorship comes in many forms. There is pre-publication censorship. This includes authorial self-censorship, that is, authors limiting what they write to avoid having their works suppressed by the authorities as well as publisher censorship, in which someone working on behalf of the publisher edits out or rewrites passages that might be construed as offensive or problematic or in which the publisher tries to suppress the entire work simply by being unwilling to publish it. The requirement at different times and in different countries that a work receive a license or privilege before it can be published is yet another form of pre-publication censorship. Works deemed inappropriate not only for reasons of obscenity, but more often because of specific political or religious content, are banned from publication and their authors are sometimes even imprisoned or put under house arrest for incitement, treason, or corruption charges, essentially as a way of stilling their voices.

There is also post-publication censorship, that is, the kind of censorship that prevents a book from being acquired, let alone read. This includes publishers not marketing the book; public libraries not acquiring the book; bookstores not carrying the book; and newspapers and periodicals not reviewing the book, all of which make a particular work virtually invisible to the reading public. The more vocal form of post-publication censorship happens once the book is out there in the world being read. These include public outcry from specific groups attacking book; requests to remove the book from bookstores, libraries, and schools; and a more general condemnation by religious authorities and public officials. All forms of censorship create an environment in which authors and readers alike find themselves stymied by outside forces attempting to control what they think, let alone write and read.