What Esherick was Reading: Architecture

Wharton Esherick was a voracious reader with both professional and personal connections to the literary world. In his intimate Studio bedroom, Esherick surrounded himself with a library covering topics across art, science, philosophy, history, and literature.

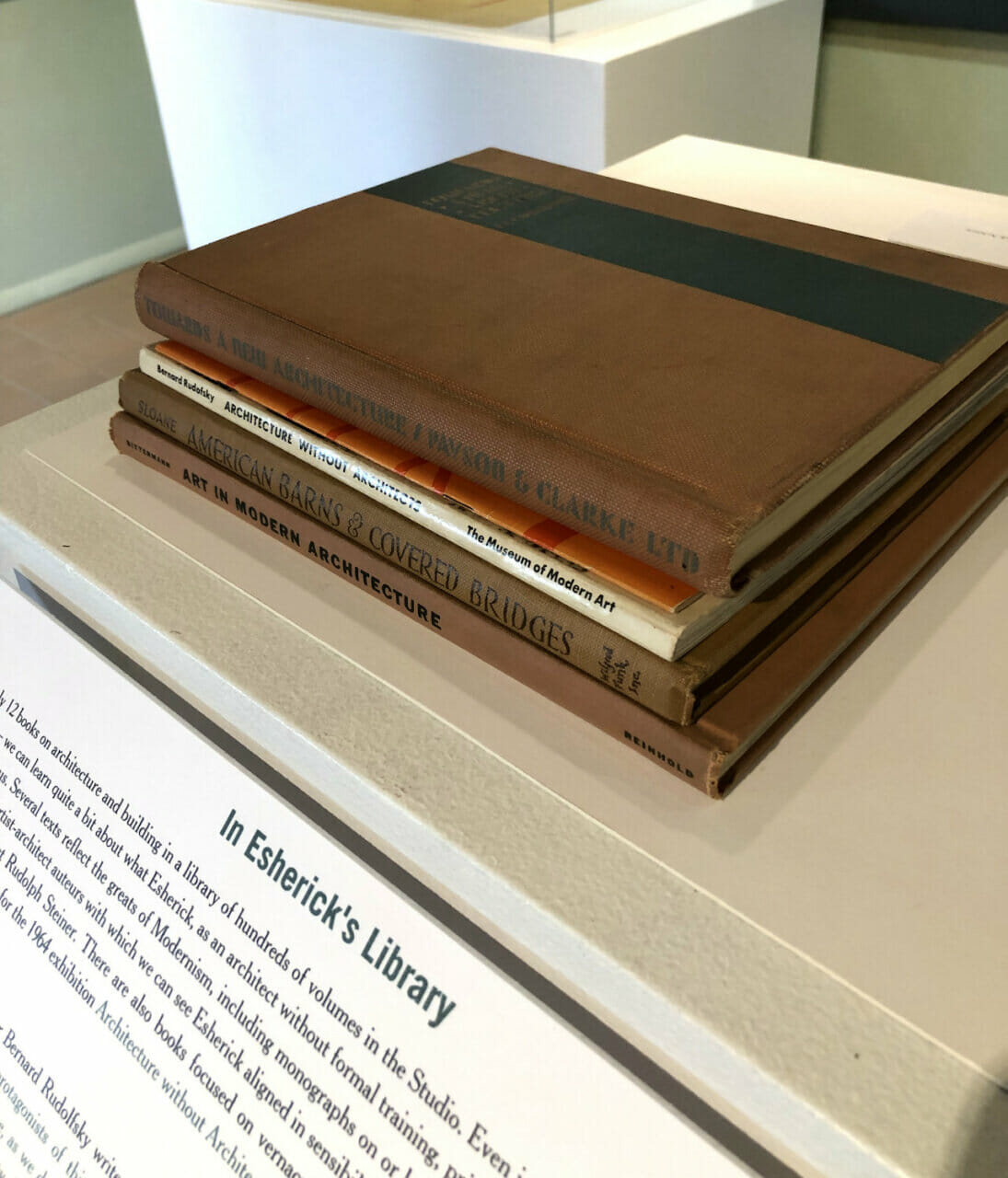

Knowing Esherick as a reader is one way of knowing Esherick as a person and artist. This makes it especially notable that within the hundreds of volumes in the Studio there are only twelve books focused on architecture and the built environment, despite Esherick designing several buildings and never receiving formal training as an architect. Several of these are currently on view in WEM’s Visitor Center as a part of the installation Home As Site.

Architectural Inspirations

Esherick’s architecture library includes several publications by important Modern architects, including two books about Frank Lloyd Wright dating from the late 1930s. Architecture and Modern Life (1937) was championed in a review from that year as an “indictment of traditional architecture, but it is also a sociophilosophical protest against the social system which has fostered it.” Esherick and Wright shared the desire to question tradition and social systems and an interest in the relationship between a building and its site. Wright introduced the word “organic” into his writings on architecture as early as 1908, cultivating a philosophy in which the architect must respect the properties of a given material and seek harmony between the form or design and function of a space. This “respect” naturally leads to an integration of all parts of a site, including between the building and its physical location, which seems highly relevant to Esherick’s architectural approach.

Fallingwater designed by Frank Lloyd Wright (1937). Photograph by Bill Hedrich. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

While Esherick famously appreciated Wright’s ideas, he was less enamored by Wright’s designs. He had more in common with the Swiss architect-philosopher Rudolf Steiner, whose Ways to a New Style in Architecture (1927) was a part of Esherick’s library. This publication reprints 5 lectures given by Steiner in Dornach, Switzerland, including plates of the First Goetheanum (where he presented these lectures), the world center for Steiner’s Anthroposophy movement, which was a major influence for Esherick. The lectures detail the spiritual, aesthetic, and material principles of anthroposophical architecture and it is easy to imagine that Steiner’s words about the Goetheaneum might apply to Esherick’s Studio itself: “Anyone who has seen even a single detail — not to speak of the whole structure, for no conception of that is possible yet — will realize that this building represents many deviations from other architectural styles that have hitherto arisen in the evolution of humanity and have been justified in the judgment of man.”

Postcards of Steiner’s first and second Goetheanum, located in Dornach Switzerland, sent to Esherick in 1928 and signed “Lou” and “L.B.” (likely from a friend of the family, Louise Bybee)

Modern Masters

Villa Savoye in Poissy, France designed by Le Corbusier (1928). Photograph by Paul Kozlowski. Courtesy of the Le Corbusier Foundation.

Other Modern architects featured on Esherick’s shelves may seem less aesthetically similar, but their presence suggests that Esherick found meaning and interest in the work. Esherick’s copy of Le Corbusier’s influential and provocative essay collection Towards a New Architecture (1929) features the famed Modernist calls for an architecture that goes beyond style and utility. Le Corbusier’s idea of the home as a “machine for living” is explored in this publication, as well as his desire to embrace technology and machine aesthetics in domestic spaces. One can imagine Esherick responding positively to Le Corbusier’s “totalizing” approach to architecture and space. As Le Corbusier writes: “The Architect, by his arrangement of forms, realizes an order which is a pure creation of his spirit; by forms and shapes he affects our senses to an acute degree and provokes plastic emotions; by the relationships which he creates he wakes profound echoes in us, he gives us the measure of an order which we feel to be in accordance with that of our world, he determines the various movements of our heart and of our understanding; it is then that we experience the sense of beauty.”

Likewise, the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto was aligned with International Style Modernism. Aalto: Architecture and Furniture (1936) expands on Le Corbusier’s ideas, moving towards “new materials and new methods of construction” (3) with an openness to organic curves and forms. Aalto’s use of wood as a primary medium and his interest in the body are both detailed in this exhibition catalog. Furniture and architecture are seen as inextricably combined, with one essay noting that for Aalto, “the creation of new furniture was implicit in the development of a new architecture” (13).

American Architecture

Texts on Modern and vernacular American architecture both appear in Esherick’s library. Built in USA: Post War Architecture (1952) accompanied an exhibition at MoMA and gives context to the emerging architecture of Esherick’s adult life exploring the standards, conditions, and 45 buildings by 32 preeminent architects of the postwar period. American architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock writes in the introduction: “Today there is no further need to underline the obvious fact that what used to be called ‘traditional’ architecture is dead if not buried” (11).

Esherick’s library also includes American Barns and Covered Bridges (1954). Author Eric Sloane not only writes about the beauty and craftsmanship of American barns and bridges of the past, but also about appreciating and finding inspiration in them into the present and future. Sloane writes: “Let it become our duty to seek out and select the authentic beauty of the past and so keep it alive for the future” (8), which Esherick did by using the visual and material language of historically rooted vernacular architecture, such as basing the form of 1926 Studio on traditional Pennsylvania bank barn construction.

Artist-Architect Auteurs

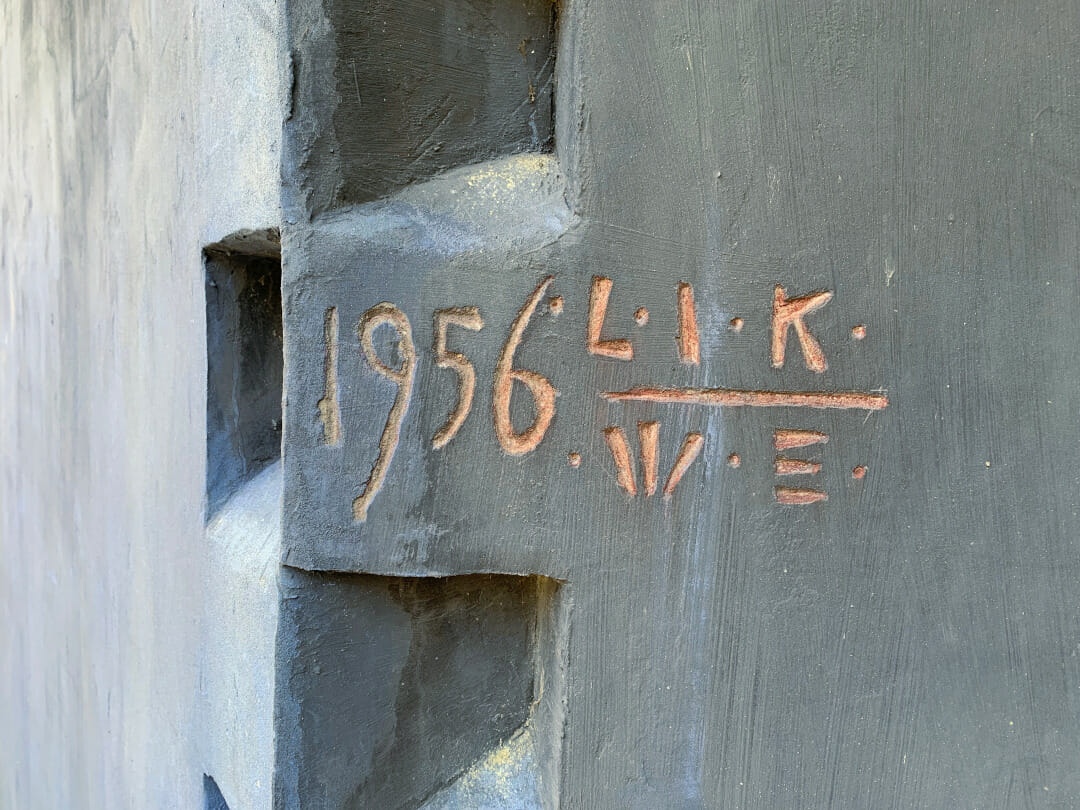

As an artist, it is no surprise to find literature on Esherick’s shelves about architects that were noted for combining art and architecture. Two publications feature Antonio Gaudi, an architect known for his distinct style incorporating color, texture, and organic forms. Gaudi (1957), a catalog of Gaudi’s work from 1957 MoMA exhibition, includes a foreword by Henry-Russell Hitchcock that puts the “bizarre eccentricities” of Gaudi’s architecture, his “preoccupation with organic forms, his enthusiasm for texture, and the alarming Hansel and Gretel atmosphere of his buildings” into context of “the discipline of the rectangular grid, and its related esthetic of form derived from pure structure.” It is hard not to draw connections between Gaudi’s curves and organic forms and Esherick’s choice to create a twisted roof over the garage or his initial curved design for the 1956 Workshop.

Esherick’s major architectural collaboration, the 1956 Workshop with Louis I. Kahn, is reflected in publications that explore how artists and architects work together. According to the introduction written by David R. Campbell in Esherick’s copy of Collaboration: Artist and Architect (1962), architects and artists might work together to “give meaning to space by relating form and use to human proportions and by rejoining the arts under one common roof.” Campbell describes this exhibition at Museum of Contemporary Crafts as “[fostering] closer relationships among all creative people who work together to produce an architecture truly expressive of our time.”

In this small selection of just twelve books from his extensive book collection, we can learn quite a bit about what Esherick – who designed and built the buildings of WEM’s campus without any formal architectural training – prioritized in his thinking about the built environment.

Titles in Esherick’s Architecture Library:

- Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Arthur Drexler (eds.). Built in USA: Post War Architecture. Simon and Schuster, New York. 1952. https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_3305_300062118.pdf

- Eleanor Bittermann. Art in Modern Architecture. Reinhold Publishing Company, New York. 1952.

- Henry Russell Hitchcock. Gaudi. Museum of Modern Art, New York. 1957. https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_3347_300190146.pdf

- Robert A. Laurer. Collaboration: Artist and Architect. Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York. 1962. https://digital.craftcouncil.org/digital/collection/p15785coll6/id/1022/

- Eric Sloane, American Barns and Covered Bridges. Wilford Funk, Inc., U.S.A. 1954.

- George R. Collins, Antonio Gaudi. George Braziller, Inc., New York. 1960.

- Rudolf Steiner, Ways to a New Style in Architecture. Anthroposophical Publishing Co., London. 1927.

- Baker Brownell and Frank Lloyd Wright, Architecture And Modern Life. Harper and Brothers, New York. 1937.

- Howard Myers (ed.), The Architectural Forum: Frank Lloyd Wright. The Architectural Forum, New York. January 1938.

- John McAndrew, 1936. Foreward. In: Aalto: Architecture and Furniture. Museum of Modern Art, New York. 1936. https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_1802_300061926.pdf?_ga=2.88735835.1925990608.1651415342-1069596895.1651415342

- Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture Without Architects. Museum of Modern Art, New York. 1965. https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_3459_300062280.pdf

- Le Corbusier, Towards A New Architecture. Payson and Clarke Ltd., New York. 1929.

Post written by Director of Curatorial Affairs and Strategic Partnerships Emily Zilber

April/May 2022