We can’t imagine talking about the holiday season without talking about traditions, and here at the museum we have a few of our own. The staff office will soon be twinkling under the glow of Christmas lights, Wharton’s leather Santa decoration will hang by the kitchen door, and our museum store shelves will be stocked once again with our holiday notecard packets. Each packet of cards holds some combination of three of the following five woodcut prints, and what’s uniquely wonderful about them (aside from being beautifully crafted) is that each is a window into Esherick’s story. So whether they are on your wish list or not, we thought they deserved a closer look!

Three of the prints are from 1923 – Christmas Snows, December and January. Stylistically, they belong together. Each depicts a snowy scene, though Christmas Snows feels more like a blizzard! The sky is made up of countless stippled marks and fine lines which sweep diagonally across the image. The house is defined with a fury of diagonal sweeps as well (which also cross in front of the trees) masterfully setting the house beyond the storm, hiding it in the swells and gusts. Thank goodness for warm fireplaces! The full title of this print is actually Christmas Snows (Dorothy Cantrell’s House). We hope to one day find the exact location, which we suspect would have been close to Wharton’s own home.

Sometimes called January- Blankets of Snow, this print depicts a calm hillside (also somewhere near Wharton’s home though we can’t say where for sure). Wharton was often capturing the changing landscape around his farm from season to season, titling prints after the various month (possibly with hopes of publishing a calendar). In January one can spot a house, or maybe two, in the distance at the edge of the field, that perhaps the lone figure is returning to. With a wonderfully economic use of line Wharton achieves the voluminous quality of the snow covering the fence which leads our gaze out over the hillside.

These prints represent some of Wharton’s earliest recognition and success as an artist. January was among one of Wharton’s prints published in The Century Magazine around this time, which would have been distributed nationwide. His woodcut prints were also published in other magazines of the period such as The Dial, The Forum, The New Republic and Vanity Fair.

December portrays another snowy day – (those blankets of snow really lend themselves to woodcut grooves!) but in this case a house with snowfall softly covering the steps, brush and branches fills the picture plane. It’s Wharton’s own home, the 19th century farmhouse which he and Letty purchased to begin their life together, and which they lovingly named “Sunekrest.” In 1923, when this print was made, the family was still young, Mary was all of seven and Ruth still a baby (and Peter a few years away!)

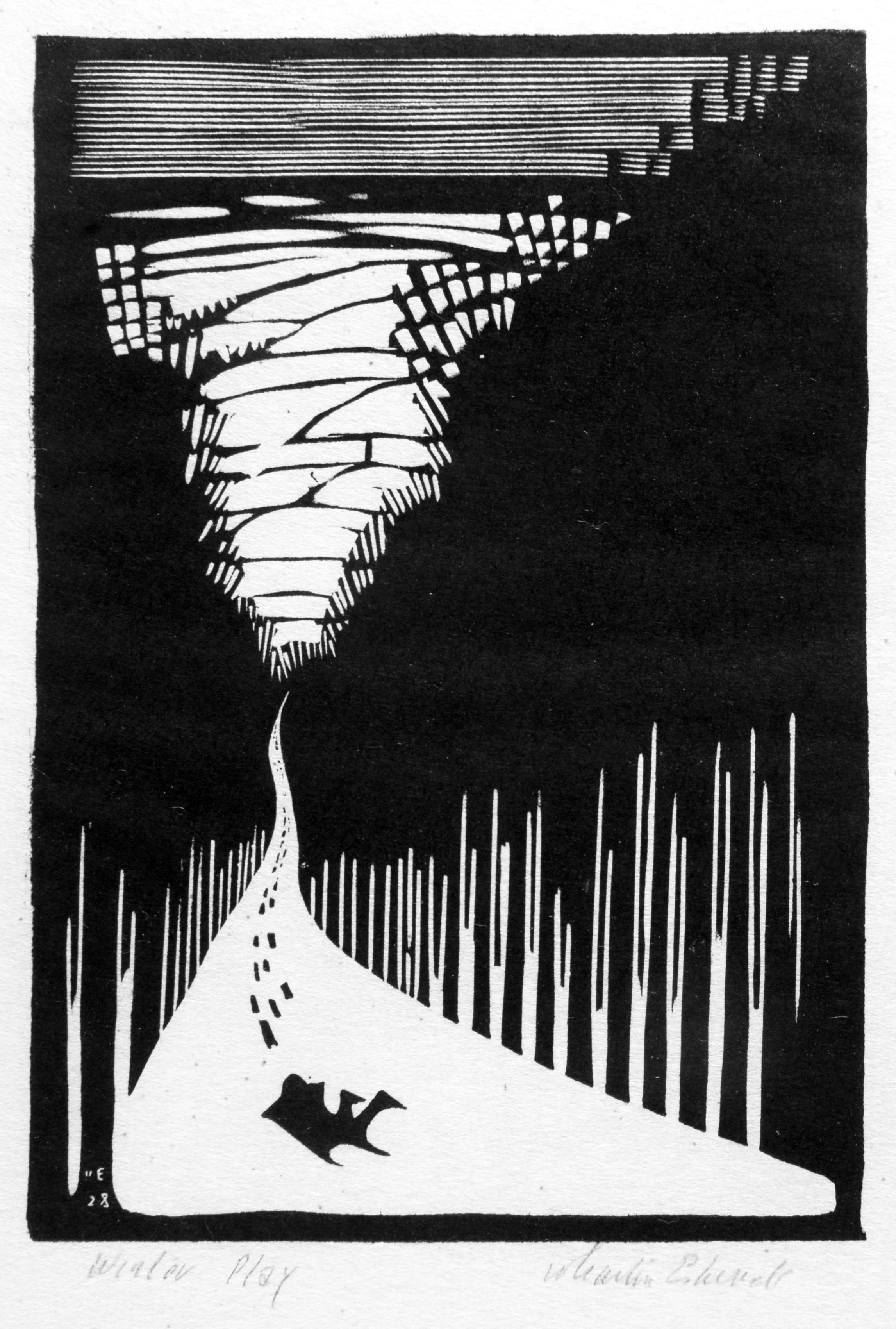

Flash forward five years and we see Ruth depicted in Winter Play, sledding down Diamond Rock Hill Road. Ruth would later recall the thrilling ride, including the little “ski jumps” made along the road by shallow trenches intended to divert rainwater, and of course, the long hike back. In the image we can see that Wharton’s style has evolved, moving closer to abstraction and further from the more traditional, representational techniques – really pushing the potential of the high contrast medium.

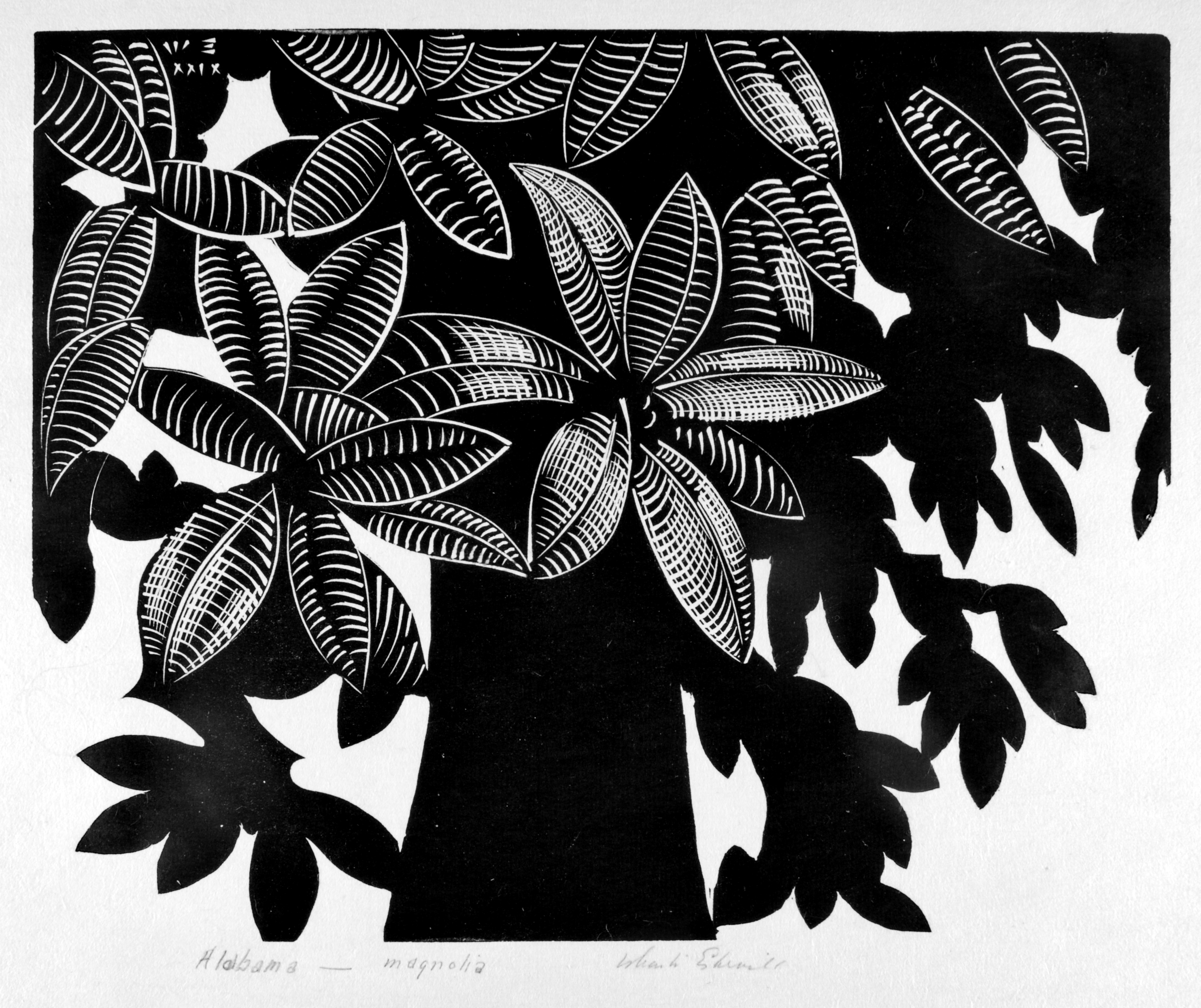

Alabama Magnolia, completed the following year, is part of a series of Alabama Tree prints conceived during Wharton’s second trip to Fairhope, Alabama in 1929-1930. (Incidentally, Wharton also worked on a series of animal garden sculptures during this trip, in collaboration with the Alabama-based potter, Peter McAdam. Wharton and Peter’s Winnie-the-Pooh is one wonderful example of their creative partnership.)

The cast aluminum version of “Winnie-the-Pooh” (ceramic original by Wharton Esherick and Peter McAdam, 1930) watches the seasons come and go!

Always a fan of trees, Wharton spent time on this trip sketching the trees of the region, including live oaks and pines, and the quintessential hanging Spanish moss. Working from these sketches, Wharton carved the blocks when he returned home to his studio. This print, as well as Winter Play and January, are actually wood engravings (the carving is done on the end grain) which allows for finer lines when carving. In Alabama Magnolia, Wharton continues with the bolder, more modern style we see in Winter Play, detailing the closest of the magnolia tree’s showy leaves, and leaving the rest silhouetted in the background. And of course, any Esherick fans down south know that wreaths made from magnolia leaves are a staple of Southern holiday decor, and make a fine edition to our notecard pack!

Post written by Visitor Experience and Program Specialist, Katie Wynne.